The dam busters: How law and science defeated developers

A history of the Environmental Defence Society.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Hamish McNicol.

A history of the Environmental Defence Society.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Hamish McNicol.

Alarm bells sounded throughout all rich nations when a group of judges at the European Court of Human Rights found in favour of a women’s group agitating for tougher climate change policies.

The case was against the Swiss government, a political entity that is the most democratic in the world. It outraged Céline Amaudruz, vice-president of the Swiss People’s Party, who called for her country to withdraw from the European court. She said the Swiss population was the boss of climate change policies, not a court in Strasbourg.

It was one of the more extreme cases of where the courts around the globe have seized initiatives that historically have been those of elected political bodies. Rather than enforce laws as they were intended, this judicial activism – or ‘overreach’ as some call it – has replaced the democratic will.

In New Zealand, judges on the Court of Appeal allowed an activist and sometime vandal, Mike Smith, to sue seven of the country’s largest corporations for their alleged contribution to climate change.

Courts deciding to interpret the law creatively is one of the most successful acts of radicalism from the late 1960s. While most students were protesting about various causes behind barricades or in street protests, as they still do today, some preferred to study law.

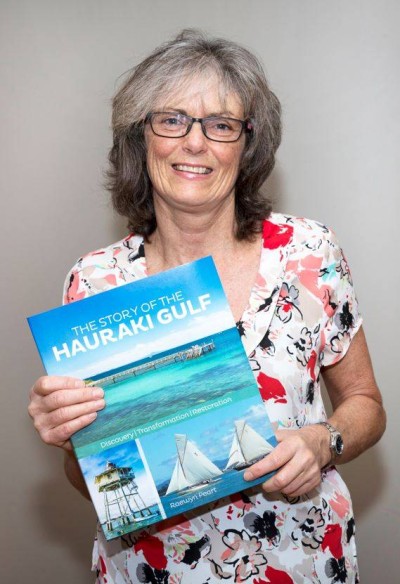

Raewyn Peart with her book on the Hauraki Gulf. Photo: Tanya Peart.

That generation of lawyers radicalised the judiciary in ways that are the envy of the most anti-capitalist trade unionist or free-market reformer. The story of this revolution is not widely acknowledged because it happened in supposedly conservative courts.

Some will say courts handling employment, family, and other discrete areas have their own form of radical capture. But my focus is on environmental law, where decisions over the past 50 years have left a legacy that rivals that of any other jurisdiction.

In New Zealand, the focus of environmental protest was the raising of Lake Manapouri for a power station to supply an aluminium smelter at Tiwai Point near Bluff.

Williams suggested a version of America’s Environmental Defense Fund, which was active in bringing cases against government agencies and businesses. The EDS soon had a patron, Sir Guy Powles, and forged a close relationship between scientists and law school academics at the University of Auckland.

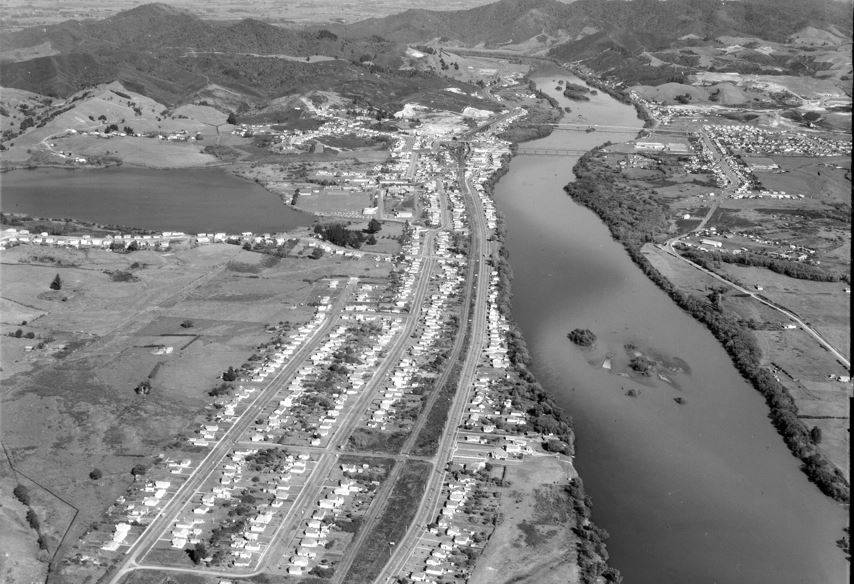

The established champions of environmentalism, such as Forest & Bird and the Civic Trust, lacked the kind of skills the EDS espoused. It lodged its first legal action over the Huntly District Council’s rights to discharge raw sewage into the Waikato River by finding a legal loophole between the expiry of the discharge rights and the implementation of the new Water and Soil Conservation Act.

Huntly in 1961 when raw sewage was discharged into the Waikato River. Photo: Whites Aviation/Alexander Turnbull Library.

The established champions of environmentalism, such as Forest & Bird and the Civic Trust, lacked the kind of skills the EDS espoused. It lodged its first legal action over the Huntly District Council’s rights to discharge raw sewage into the Waikato River by finding a legal loophole between the expiry of the discharge rights and the implementation of the new Water and Soil Conservation Act.

The case went to the Supreme (today’s High) Court, where Justice Mahon upheld a breach, sending it to the Magistrate’s Court for sentence. The council then went to the Court of Appeal and won. But the EDS had made its point. The council agreed to a treatment plant and the practice soon ended.

It was the beginning of many actions over water quality and management. Another prescient move was against the use of agricultural chemicals and the long-running campaign to ban the herbicide 2,4,5-T, better known as Agent Orange.

The dioxin-producing chemical was manufactured by Ivon Watkins-Dow in New Plymouth and was linked to birth deformities. The first legal action in 1972 was launched through Russell McVeagh, the high-powered Auckland legal firm that nurtured the EDS. By 1986, the chemical was banned.

Energy was next on the list, with the EDS drawing on scientific evidence to oppose nuclear power, questioning sites for thermal power stations, and urging higher standards for LPG storage.

An early EDS advocate, Stephen Mills (now KC), explained the modus operandi in 1977: “… [C]ourt action ought to be a lesson to Government on the ability of the Society [EDS] to use the law carefully to block projects which, on the basis of widespread public opinion and scientific and legal evidence, are ill-conceived and unacceptable.”

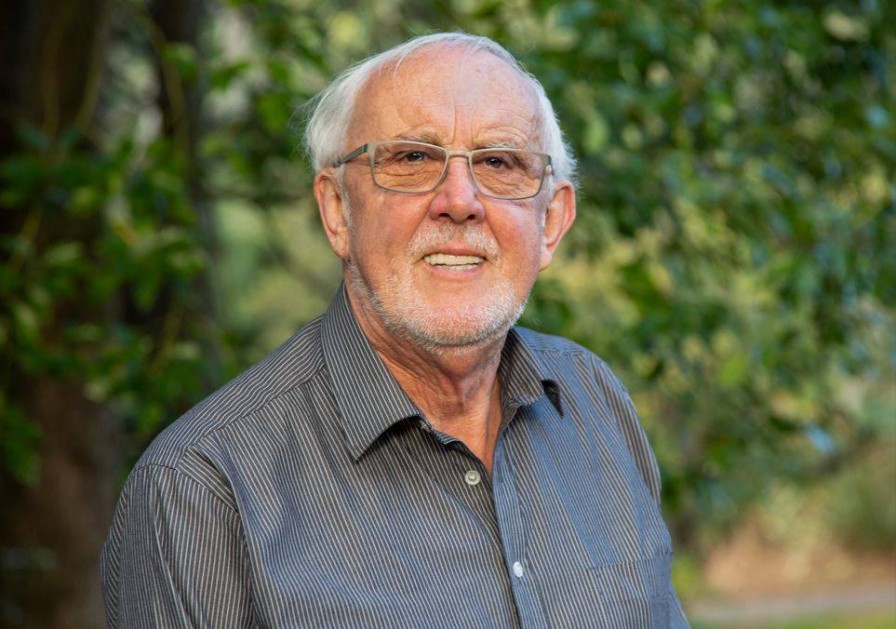

Gary Taylor joined the EDS in 1978. Photo: Raewyn Peart.

The EDS moved into higher gear with the arrival of Gary Taylor in 1978. He was neither a scientist nor a lawyer, but his communication and publicity skills put the EDS at forefront of opposition to the “think big” projects of the Muldoon government.

An early casualty was the Aramoana aluminium smelter proposal. Another was the Social Credit Party, which supported the Government’s railroading of the high dam proposal at Clyde.

The party’s two MPs lost their seats in 1982 and never returned to Parliament. Clyde was eventually finished in 1993, costing much more than planned and running into many engineering problems as its critics had warned.

EDS opposition to mining activities was less successful, though Peart states: “Legal proceedings delayed things and gradually wore the mining proponents down.” The Coromandel, apart from Waihi, escaped large-scale, open-cast mining.

Karikari golf resort replaced a proposal with 384 accommodation units. Photo: Craig Potton.

Developers of coastal land also learned the costs of this strategy. A resort proposal for 384 accommodation units at Karikari in Northland was abandoned in 1989, though it was revived much later in a far less grandiose scheme, with just 14 villas and a golf course.

Meanwhile, Taylor was becoming active as an elected councillor in Auckland. A sympathetic Labour Government disbanded the Ministry of Works – a strong advocate of state-sponsored development – and created separate entities for the environment and conservation.

EDS went into abeyance until 1999, eight years after the Resource Management Act. Taylor was soon back in the fray, however, spurred by development proposals at Pakiri Beach, north of Auckland.

Secure funding allowed the EDS to engage at the highest level with the Government as climate change and the emissions trading scheme became primary issues. Peart joined in 2001 as the EDS began a second life that “trained a whole cadre of young lawyers” – many of them making careers in environment law and even becoming members of the judiciary.

Lake Tekapo and the unique landscape of the Mackenzie Basin. Photo: Raewyn Peart.

The roll call of legal activity in the first two decades of the new millennium contribute most of the book’s nearly 400 pages. Apart from areas already cited, EDS also became involved with ocean management (such as Akaroa’s dolphins and Marlborough aquaculture), fisheries management, protection of significant natural landscapes (which sank many proposals such as Taupo’s Mapara Valley and curbed dairying in the Mackenzie Basin), and keeping rivers clean.

For farmers wanting dams and irrigation schemes for protection against droughts and floods, the EDS was a force to be reckoned with. Dams at Coalgate in Canterbury and at Ruataniwha in Hawke’s Bay weren’t built.

In some cases, EDS was called in when local opponents had run out of options. At other times, EDS sought alliances with investors and businesses to advance environmental concerns, though sometimes these failed when the gap between differing interests proved too great.

Some of Northland’s coastal developments involving wealthy and high-profile entrepreneurs such as Peter Cooper (Mountain Landing) and Craig Heatley (Bentzen Farm) engaged with EDS from the start.

This brought criticism but Peart explains the rationale: “[I]t seemed better to work with benign developers to lock in low-intensity development with associated restoration benefits rather than leaving the land vulnerable to poorly designed intensive development…”

Of course, there are two sides to the story of defending the environment. The costs and time wasted getting approval for any development have held back the economy with incalculable opportunity losses. Drought and flood-stricken farmers in Hawke’s Bay are just one set of those victims.

Much of this was due to a case involving New Zealand King Salmon’s aquacultural business in the Marlborough Sounds. It went all the way to the Supreme Court, which “turned more than 20 years of resource management practice on its head,” Peart states.

Port Gore in the Marlborough Sounds. Photo: Shellie Evans.

This was because EDS advocate David Kirkpatrick (who was appointed a judge of the Environment Court before the Supreme Court’s decision) had argued the requirement to “avoid adverse effects” in the coastal policy statement effectively meant no activity was permitted.

Dame Sian Elias, who presided over the court, went further than the NZ King Salmon case about a proposed site at Port Gore to apply this to all RMA case law. Early in her career, Elias had acted for Māori interests in the Karikari case and had recently given a paper on how RMA decisions had deviated from their original intention.

Efforts to overturn the King Salmon decision are behind today’s attempts to undo the RMA’s dampening effect on social and economic progress. Peart states the coalition Government’s proposal for “fast tracking” by three ministers is the next challenge for the EDS, and she lists several areas where the latest crop of young EDS lawyers will be focused.

These include the removal of protections for freshwater and biodiversity, as well as the planting of exotic forests for carbon offsets, and the spread of wind and solar farms. This story has many more years to run.

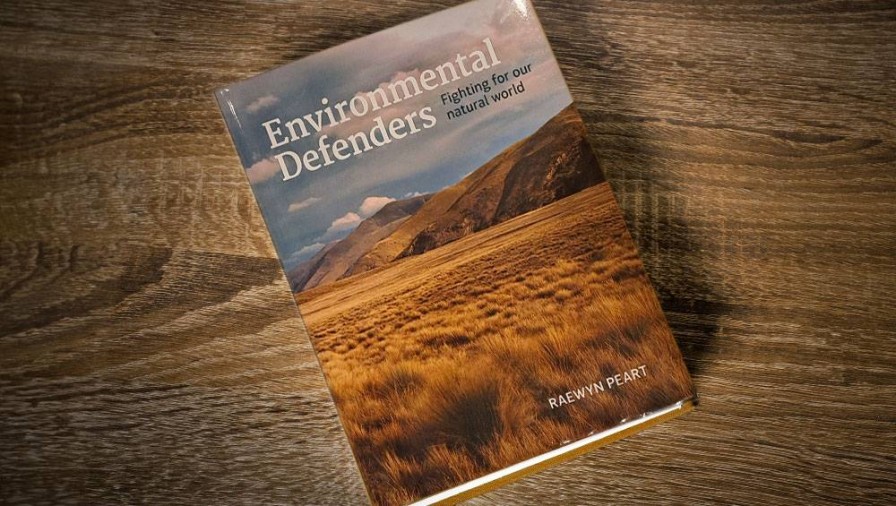

Environmental Defenders: Fighting for our natural world, by Raewyn Peart (Bateman Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.